Key Takeaways

- Depreciation recapture occurs when selling depreciated property, increasing your tax obligations.

- Profitable sales trigger taxes by converting depreciation deductions into taxable ordinary income.

- Depreciation recapture differs by property types—section 1245 (personal) vs. section 1250 (real estate).

- Strategies like 1031 exchanges or charitable trusts can legally defer depreciation recapture taxes.

If you’ve invested in property to diversify from medicine, you likely know that your asset will be susceptible to depreciation over time.

Even though the Internal Revenue Service lets you claim deductions on a depreciating property, there will be a tax reckoning when you sell it.

That reckoning comes in the form of depreciation recapture.

This article explains what depreciation recapture entails while providing tips on calculating and avoiding it.

Table of Contents

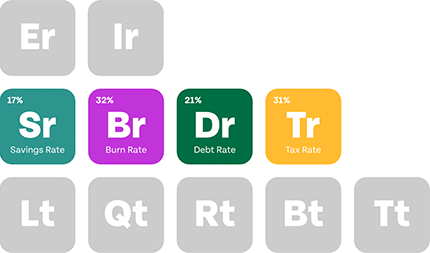

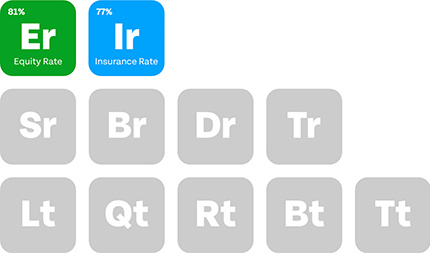

Glossary of Tax Terms

To understand what depreciation recapture entails, you must first be familiar with the following tax terms:

Depreciation

In its 2023 Publication 946, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) defines depreciation as:

“an annual income tax deduction that allows you to recover the cost or other basis of certain property over the time you use the property.

It is an allowance for the wear and tear, deterioration, or obsolescence of the property.”

Put differently, depreciation is one of many tax benefits property owners can use to lower their tax bill at the end of a calendar year.

It lets you deduct the money spent on capital improvements and maintenance or repairs on your property or asset as an annual depreciation expense.

How long you can make said deductions depends on the IRS’s specific depreciation schedules.

The property you intend to depreciate must meet the following criteria:

- “It must be property you own.

- It must be used in your business or income-producing activity.

- It must have a determinable useful life.

- It must be expected to last more than one year.”

Having a determinable useful life means the property is “something that wears out, decays, gets used up, becomes obsolete, or loses its value from natural causes.”

The IRS determines how long a useful life is for different property types.

For example, a residential rental property has a useful life of 27.5 years.

In contrast, a nonresidential real property has a 39-year useful lifespan.

You can begin accounting for the depreciation deductions on your property when it’s “placed in service”, i.e., when you start using it.

Conversely, depreciation ends once you’ve “recovered your cost or other basis or when you retire it from service, whichever happens first.”

Filing IRS Form 4562 annually lets you use this tax provision.

Basis

The IRS defines basis as “the amount of your capital investment in property for tax purposes.

Use your basis to figure depreciation, amortization, depletion, casualty losses, and any gain or loss on the sale, exchange, or other disposition of the property. In most situations, the basis of an asset is its cost to you.”

Before depreciating your property, you must account for events that result in changes to your basis in it.

As the IRS puts it “…before figuring allowable depreciation, you must determine your adjusted basis in that property.

Certain events that occur during the period of your ownership may increase or decrease your basis, resulting in an “adjusted basis.”

Examples of events that can cause changes to your basis include costs incurred while improving the property’s value and losses due to theft.

The former event will cause an increase in your basis while the latter results in a decrease.

Capital Gains

A capital gain, for tax purposes, is any profit earned on the sale of an asset after deducting costs. The IRS describes it as follows:

“You have a capital gain if you sell the asset for more than your adjusted basis.”

There are two types: short and long-term capital gains.

Short-term gains apply to property you’ve owned for less than a year, whereas long-term gains apply to tax property owned for a year or more.

This distinction will be important when calculating depreciation recapture.

What Is Depreciation Recapture?

Depreciation recapture is a tax process that lets the IRS “recapture” depreciation deductions from you when you sell an asset at a profit.

It applies to property owners who own depreciable property, whether or not they’ve used depreciation to offset taxable income in the years before a sale.

How Depreciation Recapture Works

As mentioned above, the IRS allows people who own depreciable property to claim deductions on them.

These deductions are removed from an individual’s ordinary income when they file for depreciation (via Form 4562).

Even though the idea behind depreciation is to get back the money spent on curtailing a property’s gradual loss in value, the IRS understands that some capital assets (like real estate property) will appreciate over time.

If that happens to your property before you sell, you’re legally obligated to report this taxable gain.

The usual practice would be to pay capital gains tax on the profit made and call it a day.

However, that process wouldn’t let the IRS recapture the accumulated depreciation deductions you claimed annually while holding the asset.

Hence, instead of reporting the entire profit as a capital gain, you must report part of it as ordinary income.

Under that arrangement, you’ll be liable to pay ordinary income tax rates up to your adjusted basis in the property and capital gains tax.

It’s worth noting that the IRS distinguishes between allowed and allowable depreciation.

Allowed depreciation is depreciation you’ve already deducted, while allowable is what you’re entitled to deduct.

The implication of the latter depreciation is that “If you do not claim depreciation you are entitled to deduct, you must still reduce the basis of the property by the full amount of depreciation allowable.”

Depreciation Recapture and the Internal Revenue Code

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is the extant legislation that governs the depreciation recapture tax process.

Sections 1245 and 1250 detail the types of property that qualify for depreciation and how the IRS views gains that are liable to depreciation recapture.

For example, section 1245 (1) (a) (1) states:

“Except as otherwise provided in this section, if section 1245 property is disposed of the amount by which the lower of-

(A) the recomputed basis of the property, or

(B)(i) in the case of a sale, exchange, or involuntary conversion, the amount realized, or

(ii) in the case of any other disposition, the fair market value of such property,

exceeds the adjusted basis of such property shall be treated as ordinary income.

Such gain shall be recognized notwithstanding any other provision of this subtitle.”

The above section stipulates that any gain realized on a section 1245 property that’s sold for more than its adjusted cost basis must be treated as ordinary income.

Types of Assets

Both IRC sections (1245 and 1250) identify the types of assets that are subject to depreciation recapture.

Section 1245 assets are classified as depreciable personal property, whereas section 1250 property falls under the depreciable real property classification.

Examples of section 1245 property include:

- Personal property (tangible and intangible)

- Other properties, excluding buildings

- Storage facilities; and

- Agricultural or horticultural structures

Meanwhile, section 1250 property encompasses real estate in its many forms.

Knowing the difference is important because your property type determines the amount of depreciation that’s recaptured.

Also, if you treated Section 1250 property like Section 1245 property or vice versa, you can’t change its use when filing for depreciation recapture.

Calculating Depreciation Recapture

The first step to calculating the depreciation recapture you owe is identifying your property type.

You either have a section 1245 or 1250 property. It’s worth remembering that it’s possible to mistake section 1245 properties for those classified under section 1250 of the IRC.

For example, while a research facility is unmistakably real property, the IRC views it as a section 1245 property.

Thus, read those two IRC sections to determine which umbrella your property falls under before moving ahead with your filing.

Once you determine your property type, calculate your cost and adjusted basis in it.

Your cost basis will be the amount you originally paid for it.

Meanwhile, the property’s adjusted basis is its cost basis minus the sum of all deductions made throughout its lifespan.

After you calculate your property’s adjusted basis, you can determine the depreciation recapture payable by subtracting it from the price you sold it for.

Example Depreciation Recapture for a Section 1245 Property

Imagine that you bought a research facility for $100,000 and have owned it for five years.

During that time, you’ve claimed $3,000 in depreciation deductions annually. In year six, you sell it for $110,000.

Calculating your adjustment basis would involve deducting the purchase price from the depreciation deductions, as follows:

$100,000 – $15,000 (i.e., $3000 x 5 years) = $85,000

Your gain will be the difference between the property’s sale price and the adjusted basis:

$110,000 – $85,000 = $25,000

In this scenario, your gains exceed your deductions by $10,000 (i.e., $25,000 – $15,000).

Thus, this $10,000 gets taxed as ordinary income and the remainder as capital gains.

Can You Legally Avoid Depreciation Capture?

Yes, you can avoid depreciation recapture by using different legal loopholes, like:

- 1031 Exchange: Also called “like-kind exchange”, this depreciation recapture avoidance method involves using your sales proceeds to purchase a like-kind replacement property. The purchase lets you defer capital gains tax and recapture, though 1031 exchanges apply exclusively to real property.

- Leave the Sale to Your Heirs: Rather than sell during your lifetime, try holding onto your property until death. Doing so steps up your property’s basis to its fair market value at the time of your passing and eliminates your depreciation deductions. When your heirs sell, they won’t have to pay non-existent depreciation recapture and capital gains.

- Sell While in Lower Tax Bracket: If you expect to be promoted with higher pay, now may be a good time to sell your property. This drastic avoidance method involves selling while you’re in a lower tax bracket. The lower bracket means you pay less on the part of your gain that the IRS views as ordinary income and possibly the capital gains portion.

- Charitable Remainder Trust: Some property owners avoid depreciation recapture by placing their business properties in a charitable remainder trust. This type of trust can legally sell the property without paying taxes or depreciation recapture on the profits, making it worth investigating if you have the funds.

- Invest Your Profits in a Qualified Opportunity Fund: Parking your sale proceeds in a qualified opportunity fund can be an excellent way to defer capital gains tax. While not the most affordable method, it lets you do good while avoiding taxes, since these fund types focus on investing in distressed economies.

Consult a tax expert to learn more about how you can reduce your tax bill and avoid depreciation recapture.

Final Thoughts

Reimbursing the IRS via depreciation recapture can be a complicated process, not helped by inscrutable tax jargon and property classifications.

However, the right expert advice can help meet your tax obligations without landing on the wrong side of the law.

Physicians Thrive has such experts who are well-versed in tax legislation and filing procedures.

Contact us today to get a consultation on your particular depreciation tax situation.